David v. Goliath?

| Hellespont spit | 40 11 47.04N 26 24 07.20E | This is the only point that corresponds to Herodotus' description of the site of Xerxes' bridges. |

| Xerxes' Canal | 40 22 41.70N 23 55 29.77E | Drop the "little man" at this precise point to enter Google Street View and you will see a road sign identifying the canal, which follows the line of the road SSW across the peninsula. |

| Casthanaea | 39 35 07.35N 22 55 35.35E | Now known as Kasthanea, it is a tiny fishing village. |

| Cape Sepias | 39 11 14.09N 23 21 04.23E | The cape marks the point at which you have reached the end of Magnesia and start to turn west. |

| Artemisium | 39 00 25.05N 23 12 32.65E | The Athenian fleet was drawn up on the beach here while the Persian fleet was destroyed by storms. |

| Salamis | 37 57 26.68N 23 33 20.52E | These coordinates put you right in the middle of the strait where the battle was fought. |

| Xerxes' throne | 37 58 03.46N 23 33 22.25E | The probable location of Xerxes' throne as he watched the battle. |

The story of Salamis, as told by Greek guides and graecophile websites, is of the plucky little Greek navy battling against overwhelming odds to snatch a last-minute victory from the jaws of the mighty Persian war machine. It is, of course, a tale to make the pulse quicken and the blood flow faster in the veins of every Greek, but is it true?

Herodotus is our source closest to the events and he wrote his history in order to set out the origins and course of the war between the Greeks and Persians. At the very least we should treat his figures with respect. This is what he says about the Persian fleet.

The triremes amounted in all to twelve hundred and seven.

Herodotus: Histories vii.89

Against this was the Greek fleet:

Most of the allies came with triremes; but the Melians, Siphnians, and Seriphians, brought penteconters. The Melians, who draw their race from Lacedaemon, furnished two; the Siphnians and Seriphians, who are Ionians of the Athenian stock, one each. The whole number of the ships, without counting the penteconters, was three hundred and seventy-eight.

Herodotus: Histories vii.89

So it certainly seems that the myth is true - 1,200 ships against a mere 382 if you count both triremes and penteconters.

However that is not the whole story, for before the battle of Salamis there was the battle - or rather, battles - of Artemisium. As the Persian fleet sailed down from Thessalonika (then known as Therme) to Artemisium, which is where the Greeks had determined to meet them, they stopped for the night half-way down the Mt Pelion peninsula, and that is where disaster hit them.

The fleet then, as I said, on leaving Therme, sailed to the Magnesian territory, and there occupied the strip of coast between the city of Casthanaea and Cape Sepias. The ships of the first row were moored to the land, while the remainder swung at anchor further off. The beach extended but a very little way, so that they had to anchor off the shore, row upon row, eight deep.

Herodotus: Histories vii.188

If you do a search on Google Earth, you will see that along the greater part of the peninsula between Casthanaea and the end point, Cape Sepias, the coastline is rocky cliffs. There are only two places where you have a sandy beach of any extent and one of them, Melane, is significantly shorter than the other, Pilio. I assume, therefore, that the Persians rested for the night at Pilio. The total length of available beach is 1.5 miles, but if we ignore the bit north of the little headland, we have 1.1 miles. (This compares with 0.7 miles at Melane, a beach which is also divided by a small headland.)

The next thing we need to work out is the amount of beach required by a trireme. We can gain a clue by considering the canal dug by Xerxes across the Mt Athos peninsula.

Xerxes issued orders that a canal should be made through which the sea might flow, and that it should be of such a width as would allow of two triremes passing through it abreast with the oars in action.

Herodotus: Histories vii.24

It is highly unlikely that Xerxes would want to have his triremes rowing through the canal side by side, but much more likely that he should want two-way traffic, so Herodotus' statement should be interpreted that the triremes passed each other, not passed through the canal.

Fortunately this canal can be traced on the ground and surveys reveal that it was 30m or 100 feet wide.

The canal is completely covered by sediments, but its outline is visible from air photos, and has been detected by several surveys. The total length of the canal was 2 km, its width was 30 meters, and it was 3 meters deep, enough for a trireme to pass.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xerxes_Canal

We conclude that a trireme with its oars out occupied a width of 50'. That means that along the 1.1 miles of beach at Pilio you could fit 116 triremes or 150 for the entire beach. Eight rows of one hundred and fifty ships comes very neatly to 1200 - the number of ships in the fleet.

However it may well be argued that because the beach was the safest place, as many ships as possible would want to cram themselves onto it. It is also highly dubious that the ships at anchor would be a mere fifty feet apart. Ships need room to swing as the wind or tide takes them, so the safest anchoring distance would be based on a circle whose radius extended from the point where the anchor was fixed in the seabed to the stern of the ship. Of course it is always possible that the ships were anchored fore and aft, but given that an anchor in those days consisted of a big block of stone, we may doubt that this was their method of choice.

Fortunately Herodotus gives us some further information, this time when he is talking about the bridges Xerxes had built across the Hellespont or Dardanelles.

Midway between Sestos and Madytus in the Hellespontine Chersonese, and right over against Abydos, there is a rocky tongue of land which runs out for some distance into the sea. ... Now it is seven stadia across from Abydos to the opposite coast.

Herodotus: Histories vii.33, 34

The narrowest point of the Dardanelles is from the city of Canakkale to the other side and that is, indeed, approximately seven stadia across. However there is no rocky tongue of land there. Furthermore, Canakkale is near the entrance to the Dardanelles, which may be why the first bridges were swept away by a storm - after which Xerxes famously ordered the architects to be beheaded and the water scourged amd fetters thrown into it as a reminder to the sea who was its master. (I seem to recall the King Canute of Britain employed a similar method of demonstrating his superiority.)

About 3.5 miles further up the channel - and round a sharp curve to the left - there is indeed a rocky spit of land that sticks out into the Hellespont. At this point the channel is slightly wider - 1.2 miles, though if the ancient sea level was significantly lower, we might be able to reduce that to a mile.

They joined together triremes and penteconters, 360 to support the bridge on the side of the Euxine Sea, and 314 to sustain the other.

Herodotus: Histories vii.33, 34

I think it is safe to assume that the various ships were of approximately equal width and that they were put pretty close to each other in order to create the bridge. This gives us a figure of approximately 300 ships per mile. If we assume that the full length of the beach at Pilio was used, then we can cram 450 ships onto the beach, leaving 750 to form the eight lines of ships anchored off-shore.

All this may seem to be somewhat of a digression, but there is a method in my madness.

| |

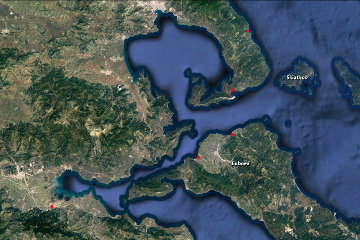

| Moving from left to right the red dots mark Thermopylae, the port of Histiaea, Artemisium where the Greeks waited, Aphidnae where the Persians anchored, and the approximate position of the Persian fleet when it was hit by the first storm. |

While the ships were anchored at Pilio a tremendous storm blew up, of such unusual ferocity that the Athenians attributed it to the intervention of the god Boreas and promptly built a temple in his honour when they reached home again.

Such as put the loss of the Persian fleet in this storm at the lowest say that four hundred of their ships were destroyed, that a countless multitude of men were slain, and a vast treasure engulfed.

Herodotus: Histories vii.190

Let's stick with Herodotus' round figures and say that 400 ships were lost. That means that Xerxes' fleet is reduced from 1,200 to 800, which rather shortens the odds at Salamis. This, however, was not the end of the Persian disasters. The Persians wanted to trap the Greek fleet at Artemisium and make sure that it couldn't retreat away to the south.

They detached two hundred of their ships from the rest, and - to prevent the enemy from seeing them start - sent them round outside the island of Sciathos, to make the circuit of Euboea by Caphareus and Geraestus, and so to reach the Euripus.

Herodotus: Histories viii.7

Once more it was the winds that came to the aid of the Greeks, for after an abortive battle in which the Persians lost 45 ships, the Greeks determined to escape under cover of darkness, but were prevented by a second fearful tempest which kept them drawn up on the beach at Artemisium.

If, however, they who lay at Aphetae passed a comfortless night, far worse were the sufferings of those who had been sent to make the circuit of Euboea; inasmuch as the storm fell on them out at sea, whereby the issue was indeed calamitous. They were sailing along near the Hollows of Euboea, when the wind began to rise and the rain to pour: overpowered by the force of the gale, and driven they knew not whither, at the last they fell upon rocks - heaven so contriving, in order that the Persian fleet might not greatly exceed the Greek, but be brought nearly to its level. This squadron, therefore, was entirely lost about the Hollows of Euboea.

Herodotus: Histories viii.13

The Persian fleet is indeed being whittled down: four hundred in the first storm, two hundred in the second and forty-five in the battle. Of the twelve hundred ships with which they started, they are now down to five hundred and fifty-five!

There was a second battle in which we are told that the "barbarians" suffered considerable loss, but Herodotus gives us no figure for the losses on either side. After this, with Leonidas dead and the Persians swarming past Thermopylae, the Greek fleet retreated to Salamis and it is there that the count was taken which showed that they still had 382 ships.

After the Battle of Salamis the Greek poet and playwright Aeschylus wrote a play called The Persians in which he tells the story of the war from the Persian point of view. In it he has Xerxes issuing the following orders to his naval commanders.

"Soon as yon sun shall cease

To dart his radiant beams, and darkening night

Ascends the temple of the sky, arrange

In three divisions your well-ordered ships,

And guard each pass, each outlet of the seas."

Aeschylus: The Persians

This is usually understood to mean that the Persians blocked the eastern strait at Salamis with three rows of ships. However the blocking cannot have been total because while the block was in place, a ship arrived from the island of Egina.

Then the captains, believing all that the messenger had said, proceeded to land a large body of Persian troops on the islet of Psyttaleia, which lies between Salamis and the mainland; after which, about the hour of midnight, they advanced their western wing towards Salamis, so as to inclose the Greeks. At the same time the force stationed about Ceos and Cynosura moved forward, and filled the whole strait as far as Munychia with their ships. This advance was made to prevent the Greeks from escaping by flight, and to block them up in Salamis.

Herodotus: Histories viii.76

| |

| The position of the Persian fleet blocking the northern harbour of Salamis, leaving the southern inlet free for ships from Egina to come and go. |

Notice the Herodotus says that the Persian fleet "filled the whole strait".

In the midst of their contention, Aristides, the son of Lysimachus, who had crossed from Egina, arrived in Salamis.

Herodotus: Histories: viii.79

Aristides informs the Greek commander, Themistocles, that there is no way for the Greeks to escape because the straits are blocked, a piece of news which was confirmed by a ship which deserted from the Persians. Furthermore, in the morning, in the clear light of day, a second ship made its way past the Persian blockade.

Having thus wound up his discourse, Themistocles told them to go at once on board their ships, which they accordingly did; and about this time the trireme, that had been sent to Egina for the Aeacidae, returned; whereupon the Greeks put to sea with all their fleet.

Herodotus: Histories viii.83

The Aeacidae were images of two particular gods who were supposed to particularly favour the Greek cause. So despite the Persian ships filling the whole strait, as Herodotus claims, two Greek ships were able to sail past them and reach the Greek fleet. They must have gone past the Persian fleet, not sailed around the other side of Salamis; if they had sailed as far as the Persian fleet, then taken flight and gone clockwise round Salamis, they would have had to cover an extra 38 miles and navigate a narrow and treacherous strait in the darkness.

And so we come to the battle itself. To make sense of what follows, it is necessary to consider the topography of Salamis. It will help if you have Google Earth open as you read this, but remember that the northern shore of the strait did not have all the jetties and wharfs which now obstruct the channel.

The town of Salamis is on the eastern side of the island, at the point where the strait turns sharply north. There are two deep inlets separated by a short, stubby peninsula and it seems to me that the town or the harbour was divided between the two inlets. The southern shore of the southern inlet is prolonged by a long, thin peninsula which is known as the Dog's Tail, which stretches out almost as far as the island of Psyttaleia, which the Persians occupied with 400 soldiers with the express purpose of killing or capturing any shipwrecked Greeks from the forthcoming battle.

The northern inlet, however, only appears to be an inlet. It is, in fact, a bay partially obstructed by an island. Anyone approaching from the east will see the island and think that it is a peninsula like the one to the south whereas in fact it is possible to sail out of the bay and head north between the island and the main island of Salamis.

Some descriptions of the battle have the Persian ships forming a line south of Psyttaleia, running in a half circle from the Dog's Tail to the mainland. That would indeed completely block the straits, but it would require more ships than the Persians actually had! Such an arc would cover approximately three miles and, at a spacing of 50' between ships, would require just over 300 ships - and if we take Aeschylus' description as accurate - and he fought at Salamis - the three lines would mean at least 900 ships. We have already calculated that the Persians only had 555 ships.

The distance from either Psyttaleia to the mainland or from the end of the Dog's Tail to the mainland is approximately one mile and that would require a mere 100 ships per line. In fact, that is about the number of ships which the Persians had available because as they were taking up station Themistocles sent a trusted slave, a Persian captured in battle some years previously who was now the tutor to Themistocles' rather unpleasant, spoiled son, to Xerxes with the message that the Greeks were planning to slip away and evade battle.

Xerxes' response was to order his men to completely block the eastern strait and to dispatch the entire Egyptian squadron round the south of Salamis to block the western strait.

Xerxes, who imagined this to be said for his advantage, was delighted, and at once gave orders to the commanders of his ships to make ready for battle at their leisure, all but two hundred, whom he ordered to put to sea at once, surround the whole strait, and close up the passages through the islands, so that no one of the enemy could escape.

Plutarch: Life of Themistokles

That means that the fleet facing the Greeks at Salamis was now reduced to 355 ships, about the right number to form three lines across the strait!

However we are still uncertain about exactly where those lines were positioned. If they stretched from the Dog's Tail to the mainland, then it would be impossible for either Aristides or the ship carrying the Aeacidae to pass. If they stretched from Psyttaleia to the mainland, that would leave the channel west of Psyttaleia and between that island and the Dog's Tail clear, but it would seem too large a gap for the Persians to overlook. No admiral worth his salt, charged with preventing the enemy's escape, would leave such a hole in his cordon.

There is a third possibility. If the Persians advanced so that their lines stretched from the tip of the peninsula between the two inlets and across to the mainland, that is a distance of 4118 ft. Three lines of that length would put the ships a mere 30 feet apart, an impossible distance if they were manoeuvring, but not at all impossible if they were stationary, on a dark night and wanting to be sure no one got between them. They may even have passed ropes from one ship to the next to help them keep station. It is also possible that the lines were curved, which would increase the ship-to-ship distance.

If this supposition is correct, it would explain two things. Firstly we may assume that the bulk of the Greek fleet lined the shores of the northern inlet, but we know that there was bad blood between some of the allies, in particular between Aegina and Athens. It is not unreasonable to think that some of the Greeks may have preferred to keep their distance and so drew their ships up in the southern harbour. They would have been easily overlooked by the Persians as they advanced in accordance with their orders to block the strait - not the inlet.

If the Athenians, with 180 ships, occupied the northern harbour, the Aeginetans, with a mere 40, might well have positioned themselves in the southern harbour and thus, when the battle began, found themselves actually behind the Persian lines! That this was in fact the case is hinted at by Herodotus' description of the battle.

When the rout of the barbarians began, and they sought to make their escape to Phalerum, the Eginetans, awaiting them in the channel, performed exploits worthy to be recorded. Through the whole of the confused struggle the Athenians employed themselves in destroying such ships as either made resistance or fled to shore, while the Eginetans dealt with those which endeavoured to escape down the strait; so that the Persian vessels were no sooner clear of the Athenians than forthwith they fell into the hands of the Eginetan squadron.

Herodotus: Histories viii.91

| |

| The Persians are lured forward, exposing their sides to the Corinthian ships from the north and the Eginetans from the south. |

The second thing is the curious tale of the Corinthian contingent.

The Athenians say that Adeimantus, the Corinthian commander, at the moment when the two fleets joined battle, was seized with fear, and being beyond measure alarmed, spread his sails, and hasted to fly away; on which the other Corinthians, seeing their leader's ship in full flight, sailed off likewise.

... They re-joined the fleet when the victory was already gained. Such is the tale which the Athenians tell concerning them of Corinth; these latter however do not allow its truth. On the contrary, they declare that they were among those who distinguished themselves most in the fight. And the rest of Greece bears witness in their favour.

Herodotus: Histories viii.94

If the Persians were blocking a line from the Dog's Tail to the mainland, they would not have been close enough for the Corinthians to see how many they were and endeavour to desert (and the desertion can only have been towards the north, as the only other route out of Salamis was east, towards the Persians!) If, however, the Persians were on the line I suggest, then not only would they be close enough for the Corinthians to see how many they were, but it would still have been possible for the Corinthians to escape northwards by sailing to the west of the small island in the bay.

There is reason to suspect, however, that the Athenians were being less than charitable towards the Corinthians, for Herodotus agrees that they played a brave part in the battle. The point is that the whole battle was a deceit: Themistocles deceived the Persians into blocking the straits (and sending part of their fleet away to block the western strait), now he did two further things to deceive the Persians.

The fleet had scarce left the land when they were attacked by the barbarians. At once most of the Greeks began to back water, and were about touching the shore, when Ameinias of Palline, one of the Athenian captains, darted forth in front of the line, and charged a ship of the enemy.

Herodotus: Histories viii.84

The Greek fleet advanced towards the Persians and then, inexplicably, began to go backwards. The Persians, not unnaturally, followed them, particularly as they saw part of the fleet hoist sail and start to flee (apparently) towards the north. Lured into Themistocles' trap, the Persians became sitting ducks. They were now to the west of the end of the peninsula, strung out in at least three lines that extended from south to north. The Athenians surged forward and by attacking the Persians ensured that the front line came to a stop and the other lines pressed forward and became more or less immobile.

At that moment the Corinthians turned about and came storming down from the north, this time passing to the east of the small island and crashing into the sides of the stationary Persian ships. At the same time the Eginetans emerged from the southern harbour and either hit the southern edge of the Persian fleet or attacked it from the rear. The poor Persians, who were approximately equal in numbers to the Greeks or possibly even inferior in numbers, didn't stand a chance. Herodotus rather smugly observes:

Far the greater number of the Persian ships engaged in this battle were disabled, either by the Athenians or by the Eginetans. For as the Greeks fought in order and kept their line, while the barbarians were in confusion and had no plan in anything that they did, the issue of the battle could scarce be other than it was.

Herodotus: Histories viii.86

In other words, the Greeks were fighting to a plan whereas the Persians were simply crowded together in confusion, hoping to overwhelm the Greeks by numbers - numbers which they no longer had and which, in any case, they could not employ in the narrow strait.

There is one final piece of evidence in favour of my location for the battle. Herodotus tells us that Xerxes was watching the whole thing and was close enough to single out individual ships for praise or blame.

During the whole time of the battle Xerxes sate at the base of the hill called Aegaleos, over against Salamis; and whenever he saw any of his own captains perform any worthy exploit he inquired concerning him; and the man's name was taken down by his scribes, together with the names of his father and his city.

Herodotus: Histories viii.90

The name "Aegaleos" is attached to a ridge which runs half a mile from the shore and today has the suburb of Perama at its foot. Google Earth has photographs attached to its various locations and if you hunt around you can find one, taken from the highest point of Mt Aegaleos and looking towards Salamis. Even large modern ships look tiny - remember, there were no binoculars or telescopes in those days - and a more unsuitable place for watching the battle can hardly be imagined.

Furthermore we know that when Xerxes wanted to encourage his troops, he was not afraid to come very close to the front line. Up at Thermopylae Xerxes was so close that:

During these assaults, it is said that Xerxes, who was watching the battle, thrice leaped from the throne on which he sate, in terror for his army.

Herodotus vii.212

I think it more likely that Xerxes leaped from his throne in terror for himself than for his army, but whichever it was, the story implies that Xerxes was close enough to the fighting to be in danger of coming under attack from the Greek soldiers.

The Aegaleos range ends in a deep gorge, beyond which the mountains continue as three ridges. The southern-most of these ridges ends in a prominent hump which stands right on the shore of the strait. I am sure that Xerxes' throne was placed part way up the southern side of this hump, which would give him a good view of the fighting and, more importantly, give his captains a good view of him. Xerxes was of the opinion that his fleet had been so unsuccessful at Artemisium because he was not there to keep an eye on them. By placing himself in a prominent position - and the main range of Mt Aegaleos is certainly not that - he intended to inspire his navy with the determination to win.

If this location is correct, then again we have the main battle taking place between the end of the peninsula and the island which sits in the northern bay.

The conclusion has to be that Salamis was not plucky little Greece battling against overwhelming odds. It was wily Greeks whittling away at the Persian fleet until, when battle was finally joined, the Greeks had the numerical advantage, which they used with tactical brilliance, luring the hapless Persians into a trap and then attacking them from west, north and south simultaneously.

© Kendall K. Down 2016