The Tomb of Christ

| |

| A typical 1st century AD |

First Century AD Jewish tombs consisted of an underground room, in the walls of which were excavated coffin-sized tunnels (kokhim) at ground level. The body was placed in one of these tunnels, which was then closed and left for a year or more until the body had decayed away completely. At the end of the year the tunnel was opened, the bones removed and placed in an ossuary - a stone box just big enough to accommodate the longest bone, the femur - and the kokh was then ready for its next occupant. This style of tomb can be seen in the so-called Tombs of the Sanhedrin, Tombs of the Prophets Haggai and Malachi, and perhaps most notably, in the Tomb of the Kings.

For the first few decades after the death of Christ there was no dispute over the location of His tomb, though whether it was in any way venerated may be doubted. More than likely Joseph of Arimathea used the tomb for its original purpose - the burials of himself and his family. Jews, who regarded tombs as unclean, are unlikely to have visited and entered the tomb, even if that was permitted, though Jewish Christians may well have pointed out its location to visitors.

Jerusalem was captured by the Romans in AD 70 and much of the city was ruined, but some, at least, of the Christian community returned from Pella and would have been able to identify the location of Joseph's tomb.

The situation was very different in AD 132 after the Bar Kokhba revolt. When it was finally put down Hadrian ordered that Jerusalem should be completely destroyed. A new city, named after himself - or rather, after his family name - was laid out on top of the ruins in accordance with Roman town planning principles, with a forum, streets arranged in a rectangular grid pattern, and temples to Roman gods.

In a deliberate affront to Jewish opinion, the main temple was built in the south-east quadrant of Aelia Capitolina, approximately on the site of the Jewish temple. A slightly smaller temple, dedicated to Venus, was built in the north-west quadrant, probably to provide aesthetic balance but possibly to desecrate an area venerated by the Jewish sect of Christians, for it was built over the site of Joseph's tomb.

When Constantine converted to Christianity two centuries later, he ordered that the temple of Venus should be demolished, the fill that underlay it removed and the tomb of Christ recovered. The trouble was that no one living knew what the tomb looked like or its exact location and as there were probably several tombs within the area covered by the temple of Venus, it is not clear on what basis one particular tomb was selected as the tomb of Christ.

The tomb was, of course, underground and Constantine's architects solved the problem of commemorating a hole in the ground by cutting away the rock around it to create a circular plaza in which stood a block of stone containing what was believed to be the tomb of Christ. (The task was not as onerous as might be thought: a circular rotunda covered the tomb and a basilica was built in front of it. The stone for these structures had to come from somewhere! What more convenient than to quarry it from the same place as the tomb?)

An area of rock only about 90 feet away was identified as the site of the crucifixion and was allowed to stand at its original level, untouched by the quarrying operations. Because it was higher than the surrounding area, it came to be known as "Mt Calvary" - the Gospels make no mention of a hill or mountain.

Constantine's church was destroyed by the Persians in AD 614, rebuilt and destroyed by an earthquake in 746, burned down in 841 and again in 966, and finally destroyed by al-Hakim, the mad caliph of Cairo. On this occasion the block of stone containing the tomb was broken up but fortunately the workmen were dilatory and abandoned the task when the broken stone filled up the area. When the new caliph, Ali az-Zahir, allowed the church to be rebuilt and the rubble was cleared away, the walls of the tomb still stood to a height of approximately two feet.

The church suffered further vicissitudes in the ensuing centuries and was repeatedly rebuilt by the Greeks and at least once by the Crusaders. During all that time no one doubted that the building housed the genuine tomb of Christ, which was venerated by all Christian denominations - Catholic and the various flavours of Orthodox.

Doubts began to be expressed with the coming of the Protestant Reformation, probably as a reaction against the many superstitions and spurious relics which had flourished under the Roman Catholic church. The first public rejection of the site was by a German pilgrim Jonas Korte, in 1743, who pointed out that the Holy Sepulchre was inside the walls of Jerusalem and could not, therefore, be genuine.

| |

| Roman tombs line the road leading into Hierapolis in Turkey. |

Roman law forbade burials inside a city's walls and every Roman city had avenues of tombs lining the roads that led from the city. Such cemeteries can be seen in Rome itself or at Hierapolis in Turkey (near ancient Laodicea), and in many other places. If the Sepulchre site was inside the walls of ancient Jerusalem, then it could be dismissed without further argument.

There was no similar ban on executions taking place inside a city, but on the whole the Romans preferred to execute criminals in some place where the sight could strike fear into the hearts of potential malefactors. A busy street or road would be ideal, but as shopkeepers were unlikely to welcome crowds of people gawping at the sight instead of patronising their shops, executions took place either in an arena or amphitheatre or beside one of the main roads outside the city. Again, we have to ask whether the Holy Sepulchre site was inside or outside the city walls in AD 31.

| |

| The caves in this quarry are supposed to resemble a skull and therefore, it is claimed, mark this as the site of Golgotha |

The present wall which surrounds the Old City was built by Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent of Turkey in 1535. Assuming that the modern walls mirrored the Roman walls, Victorian Protestants rejected the Holy Sepulchre. An alternative was identified by several visitors to Jerusalem, who noticed the appearance of a skull in the rock face of a quarry outside the north wall of Jerusalem near the Damascus Gate. The most famous proponent of this theory was General Gordon of Khartoum. Thirty years later, in 1867 a small tomb was discovered near - but not too near - Gordon's Calvary. This was gleefully declared to be the genuine tomb of Christ, a claim still maintained by the Garden Tomb Association.

There are two problems with this identification. The first is that we do not know the date of the quarry and so do not know whether it existed in the time of Christ nor whether the two caves which make up the "eye sockets" of the skull had been exposed at that time. Allied to this is the fact that the soft limestone of the Judean hills is easily eroded and a large chunk of the "nose" fell off only a couple of years ago, which implies that the cliff may have borne a very different appearance two thousand years ago.

| |

| The supposed burial place of Christ in the Garden Tomb, which is not at all like 1st century AD Jewish tombs. |

The second problem is that in 1968-71 a survey of tombs in the Jerusalem area by Israeli archaeologist Gabriel Barkey demonstrated that the Garden Tomb is typical of tombs from the 6th century BC! The Garden Tomb Association acknowledges the fact, but suggests that Joseph of Arimathea may have been constructing his tomb in an archaic style.

If - as seems inevitable - we reject Gordon's Calvary and the Garden Tomb, the only alternatives are either some yet unknown site, or the Holy Sepulchre. As history seems to point to the traditional site, much depends on the problem of where the walls of Jerusalem were in the time of Christ.

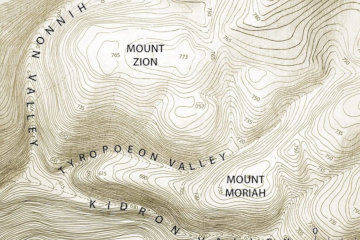

The original Jebusite city was located on the Ophel Ridge, which runs south from the Dome of the Rock and is bordered on the east by the Kidron Valley and on the west by the Tyropoean Valley. The steep sides of the valleys provided good defences which were further strengthened at some point by quarrying away the end of the ridge so that it terminated in a vertical cliff rather than a slope. The city's only weak point - the relatively flat ground to the north - was guarded by a strong wall which was so formidable an obstacle that David was only able to capture the city by sending men up the water shaft from the Gihon Spring.

Solomon built his temple on that flat ground and may even have considered that he was giving the city additional protection by making the temple of YHWH the chief barrier against any attack from that direction. It is believed that Solmon's palace stood between the south wall of the temple and the north wall of the Jebusite city.

Over time Jerusalem grew and extended to the west onto the broad ridge known today as Mt Zion. It would appear that this suburb was enclosed within a new wall by Hezekiah, probably in preparation for an expected attack by the Assyrian king Sennacherib. (Hezekiah's Tunnel was another part of those preparations, bringing the water from the Spring Gihon in the Kidron Valley, to the Pool of Siloam inside the newly expanded city.)

In the 1970s a section of wall, 22' thick and still standing 10' high was discovered in the Jewish Quarter and excavated by Nahman Avigad, who dated it to the time of Hezekiah. A wall of such a size can only have been a city wall! It is located over a thousand feet to the south of the Holy Sepulchre. This Broad Wall curves and its further course is uncertain, but the discovery, also by Avigad, of a strong tower, possibly dating to the time of Manasseh and surrounded by evidences of the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem, almost certainly shows that the Broad Wall ran north well to the east of the Holy Sepulchre.

As it is very unlikely that Hezekiah's wall ran in a 'U' shape, this means that the site of the Holy Sepulchre is outside Hezekiah's north wall on Mt Zion. However that leaves unanswered the question of the Roman wall.

According to Josephus, at the time of the AD 70 siege, Jerusalem was guarded by three walls - the original city wall of Hezekiah, the Second Wall which enclosed another area on the north of Mt Zion, and a Third Wall which was to the north of the temple area. For a long time the location of the Third Wall was a mystery, but a few years ago excavations in which the Diggings team participated uncovered what is believed to be the foundations of this Third Wall. It runs along the north side of No'omi Kiss Street and may have enclosed the Holy Sepulchre site. However the Third Wall was built after the time of Christ by Agrippa I, the grandson of Herod the Great and is irrelevant to the question of whether the Holy Sepulchre was inside or outside the walls of Jerusalem in Jesus' day.

Unfortunately the Second Wall has no such archaeological evidence and its course is very much a matter for conjecture. Josephus tells us that it ran from the Antonia Fortress, just to the north of the temple, to the towers built by Herod the Great, at least one of which is incorporated in the so-called "Tower of David" beside the Jaffa Gate. It was a short wall with only 14 towers, compared with 90 towers in the First Wall (Hezekiah's wall?) and 60 in the Third Wall. Some conjectural maps of the walls of Jerusalem show the Second Wall meandering around in an uncertain manner. Such a course would require more than fourteen towers - and it ignores the simple facts of geography.

| |

| Steps leading up on the west side of David Street. The second wall would have been at the top of this slope. |

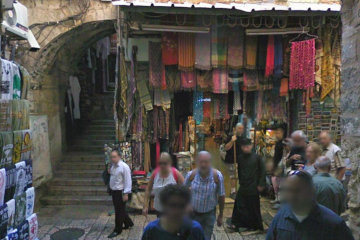

The Old City of Jerusalem is bisected on an east-west line by the Tyropoean Valley, which can be traced from the Damascus Gate down past the Wailing Wall to the Dung Gate and beyond to its junction with the Hinnom Valley. The present Western Wall plaza sits in this valley. However if you enter Jerusalem via the Jaffa Gate you will have the Tower of David on your right and directly opposite you is the entrance to David Street, a thoroughfare which runs straight across Jerusalem from north to south, crossing the Tyropoean Valley on a causeway supported (in part) by Wilson's Arch.

David Street is lined with souvenir shops and the casual visitor is distracted by the plethora of beduin costumes, olive wood crucifixes, brass ewers, mother-of-pearl brooches and endless postcards. If he were to look beyond the shops on his right, however, he would find that every so often there is a narrow alley between these shops - and the alley is made up of steps; steep steps rising up from David Street.

| |

| A topographical map of Jerusalem showing the David Street valley just to the east of Mt Zion. |

A topographical map, if you can find one, shows that David Street runs along a shallow valley that descends until it meets the Tyropoean Valley. The obvious location for a wall is at the crest of the slope on the west side of David Street so that the valley adds to the defensive strength of the wall. Such a location would be sufficiently east of Hezekiah's wall to make a useful addition to the space inside the city, and if we picture it as turning north shortly before the Tyropoean Valley and then crossing the valley to join the north wall of the temple - the probable location of the Antonia Fortress - then the resulting wall would be short enough that is could be adequately defended by fourteen towers.

If this conjecture is correct, then we can say that in the time of Christ the site of the Holy Sepulchre was outside the walls of Jerusalem - but the existence of the Wilson's Arch bridge or causeway points to another fact: there was a road giving access to the temple which roughly followed the course of David Street, at least at its eastern end. This makes sense: pilgrims from the north and from the coast would not wish to plunge into the narrow lanes of whatever lay north of the temple or in Hezekiah's suburb, but would make their way across open ground to the David Street valley and head down it, over the bridge and so into the temple.

That means that the area of the Holy Sepulchre would be an ideal spot for a crucifixion: it was relatively close to the Antonia Fortress where Pilate tried Jesus and passed sentence of death; it was on a major thoroughfare where thousands could see the fate which awaited those who pretended to be kings; it was on open ground where no one would be offended by either the execution or the gawping crowds.

However one argument against the Holy Sepulchre/Calvary site is the proximity of the crucifixion site to the tomb. Would the Romans really conduct an execution in a cemetery?

The Satyricon of Petronius Arbiter contains the story of a man who died and was buried and his devoted widow refused to leave his tomb. Shutting herself inside, with only a maidservant for company, she determined to starve herself to death. On the second day there was an execution; the criminals were crucified in the morning and by night they were dead - a detail which is given without comment as if this was the normal course of events - and a soldier was left on guard to ensure that the relatives did not remove the bodies and take them away for burial.

In the darkness of the night the soldier noticed light from the lamp in the widow's tomb, went to investigate and, to cut a long story short, offered the widow such effective comfort that when the relatives did indeed remove one of the bodies for burial, she had no hesitation in putting her husband's corpse on the cross to save her soldier lover from punishment for failing to keep a proper watch. (Satyricon CXII)

Whether or not the story is true, the point is that it was presented as at least true-to-life, indicating that there was no difficulty about an execution taking place in a cemetery. In other words, there is nothing inherently unlikely in the Tomb and Calvary being as close as the Holy Sepulchre makes them.

However there is a more serious difficulty: the grave inside the Tomb takes the form of a marble slab something like an altar. Recent rennovations of the Tomb temporarily removed the slab and revealed a limestone "bed" a foot or so lower down, which was the actual grave - but if that is so, then, like the Garden Tomb, it is nothing like the First Century tombs which, as we have already seen, take the form of coffin-size kokhim cut into the walls of the burial chamber.

The circular space which surrounds the Tomb is lined with doorways and one of those doorways, behind the Tomb, leads into a dusty and neglected room known as the Chapel of Nicodemus. On the other side of the room a second doorway leads into a small chamber which, ironically, plans of the church claim to be the Tomb of Joseph of Arimathea. Cut into the far wall of this chamber are four genuine First Century kokhim!

| |

| Typical Jewish kokhim off the Chapel of Nicodemus in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. |

If the tomb of Christ is anywhere within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre - and I hope I have shown that that is feasible if not probable - then very likely it was in one of these kokhim that the body was placed and this neglected chamber is, in fact, the holiest site in Christendom - the very place where Jesus was buried and from which He rose on Easter Sunday.

Ironic, really.

Note: My e-book, Alexamenos and Alkmilla which goes into the crucifixion of Christ from the historical and archaeological point of view is available from Kobo.

© Kendall K. Down 2022