The Ancient Curse

One of the more interesting discoveries in Egypt were the so-called "Execration Texts". Dating from a period when Egypt's physical power was declining and its armies no longer ventured across the Sinai desert into Palestine, the Egyptian priests came up with an ingenious way of helping pharaoh let off steam. If some client king wasn't coming up to scratch or an ally was proving less reliable than was thought desirable, his name was written on a pottery jar along with a whole string of curses, and then, with due ceremony, the jar was smashed while the priests recited the curses.

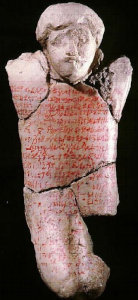

| |

| A shattered execration figurine dating to 1800 BC. |

The earliest execration texts, dating from the 6th Dynasty, were written on stylised models of Canaanite kings. It wasn't until the Middle Kingdom that pots were used - possibly because they were more satisfying to smash. One may wonder just how effective a curse would be if the solid baked clay figurine only suffered minor damage when pharaoh hurled it to the ground!

Whether or not the curses were effective, we value the texts because they give us an interesting insight into Egyptian power politics of the time, mapping out the waxing and wavning of Egyptian influence among the petty rulers of Palestine and Canaan. In particular, the texts provide evidence for the existence of places for which there is no archaeological evidence! For example, execration texts from Middle Bronze IIA mention Jerusalem, Shechem, Hazor and Beth Shean, but archaeologists have found no MBIIA remains in those places!

I don't know whether the Egyptians were the first to create written curses, but they were by no means the last. The custom of writing curses on strips of lead was popular in Roman times; for example 120 such "curse tablets" were found in and around the Roman baths at Bath, in England. Others have been found in London and around Hadrian's Wall. A surprising number had to do with property disputes or losses - if something was stolen from you by persons unknown, in the absence of Sherlock Holmes you had to be satisfied with writing out a fearsome curse on the perpetrator and nailing the strip of lead in a nearby temple or throwing it into a spring.

The first curse tablets ever found came from the Greek colony of Selinunte in Sicily, but hundreds have been found in various locations in Greece itself - so many that prissy classical scholars prefer the term "judicial prayers".

| |

| The curse tablet dating to AD 130 and found at Bath, dealing with the woman Vilbia. |

Of course, it wasn't only goods and chattels that could be stolen and a surprising number of these tablets concern rivals in love. One, found at Bath, states, "May he who carried off Vilbia from me become liquid as the water. May she who so obscenely devoured her become dumb." Others seem to take the form of love charms, seeking to attract the named person - male or female - to the creator of the tablet. Christopher A. Faraone has analysed these tablets and concluded that they fall into two categories: those which seek to excite passion and those which ask for affection from their subject. It will hardly be surprising to learn that it is men who seek passion and women who want to stimulate affection.

Back in 2019 a group called Associates for Biblical Research was ecavating on Mt Ebal, near Nablus. The area had already been pretty thoroughly dug by Israeli archaeologist Adam Zertal twenty years earlier, but on the basis that new techniques can reveal things from that which was regarded as rubbish even only two decades earlier, the Associates, under Dr Scott Stripling, excavated the spoil heaps from Zertal's excavations. They took the trouble to wash all the dirt, and as a result found a tiny lead tablet.

Of course, in such an excavation there is no chance of any meaningful stratigraphy and anything found has to be assessed on its own merits, rather than in the context of where it was found. Nevertheless, in this particular excavation, the dates were fairly well known, for Zertal had dated his original excavation to the time of Joshua (which by conventional chronology is Iron I), but others prefer several centuries later in Iron II. In either case - either 1400 BC or 1200 BC - it is the earliest Hebrew writing known.

| |

| The leaden curse tablet from Shechem found by Dr Scott Stripling and his team. |

Chemical analysis of the lead shows that it came from a mine in Greece which was active during both those periods. The form of the letters also support these early dates, for they can be identified as proto-Hebraic or as Sinaitic, the script used at the turquoise mines of Serabit el-Khadem. Before this, the earliest Hebrew text was a tablet found at Khirbet Qeiyafa, overlooking the site of David's victory over Goliath, which dates to 1000 BC.

The curse tablet took the form of a strip of lead that had been folded to make a lump about 2cm x 2cm. Unfortunately the lead was far too fragile for the archaeologists to even attempt to open it up and they had to take it to a specialist lab in the Czech Republic, which scanned it in a process similar to an MRI scan of a human body, thus enabling the letters scratched into the lead to be read. Unfortunately it is not all that clear whether the letters were written from right to left or left to right - or even up and down - and the archaeologists have devoted considerable time trying to make sense of the inscription. This is their best guess:

Arur Arur Arur

Arur la’El Ye’ho

Tamut – Arur

Arur – Mot Tamut

Arur l’Ye’ho

Arur Arur Arur

"Arur", apparently, means "curse" or "cursed" and the tablet would be highly significant as testimony to literacy at that early period in Israel's history. Some sceptics have claimed that "of course" very few people or even no one at all could read and write in early Israel and therefore the books attributed to Moses and Samuel *must* have been written at a much later date. We can now show, both from Khirbet Qeiyafa and this new discovery, that people could read and write and that the skill wasn't restricted to a few professional scribes - for the writing on the new tablet is so rough that it cannot be attributed to a scribe!

However the real killer comes in the second line of the inscription, where you have both Yahweh (in the form Ye'ho) and Elohim (abbreviated to El) appearing together. Roughly translated, the line reads "cursed by Yahweh Elohim" (or "cursed by the God Yahweh").

Back in the 1800s some German crank called Wellhausen came up with the theory that the book of Genesis had multiple authors. One of them always referred to God as "Yahweh", another always referred to God as "Elohim", and it was a much later editor who combined the two names as "Yahweh Elohim". Like all conspiracy theorists, his ideas were based on ignorance - though I suppose we can't be too hard on him for not taking into account a discovery made a century and a half after his death!

Here we have a document dating to well before Wellhausen's putative authors and editors, casually using "Elohim" and "Yahweh" in the same breath. In other words, the new discovery supports the idea that Moses could have written his books, because literacy in the new proto-Hebraic system was widespread, and it also shows that Moses didn't need additional authors and editors to account for his use of the names of God.

© Kendall K. Down 2022