Archaeology and the Bible

Exodus - 1

| Il-Lahun | 29 14 10.48N 30 58 14.42E | The picture is not the clearest on Google Earth, but the much eroded pyramid can be seen, together with the "Queen's Pyramid" behind it, beside which is the row of mastabas. |

| Kahun | 29 14 05.37N 30 58 30.07E | There is nothing to distinguish the site of the village of the pyramid builders, particularly on such a poor picture, but my recollection is that it is on the ridge near the junction of the two dirt tracks. |

| Pithom | 30 33 11.90N 32 05 57.36E | The outline of an enormous rectangle - doubtless the walls of a town or fort - can be seen. This is as fine an example of crop-markings as you will find. It is not clear, however, whether these coordinates (taken from Wikipedia) refer to Tel el-Maskhuta or Tel ar-Rebata. |

| Avaris | 30 47 11.12N 31 49 19.82E | The coordinates are taken from Wikipedia, for there are no photographs to mark the site, which seems a little strange. Tel el-Dab'a is believed to be Rameses, one of the cities built by the Israelites in Egypt. Excavations and ruins can be seen in the picture. Visit the Avaris website for a map of the site. |

| Adabiyeh | 29 51 47.73N 32 30 30.91E | Unfortunately Google Earth has stopped showing detail over the sea, so you cannot see more than the start of the underwater ridge which runs north-east to the opposite shore. |

Language

With the exception of the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, nearly all the Old Testament is written in Classical Hebrew, which was current between the years 1000 BC and 600 BC in conventional chronology. That means, from the reign of David to the Exile. The two exceptions are the Song of Miriam, in Exodus, and the Song of Deborah in Judges, which appear to be in an archaic form of Hebrew.

Unless we postulate that Classical Hebrew was in use in the time of Moses, we are obliged to conclude that a later scribe revised the documents that Moses wrote, putting them into contemporary language, but leaving poetry untouched in much the same way as a modern editor might put an Elizabethan text into modern language but preserve any quotes from Shakespeare exactly as they were written.

Date and Place

When considering the book of Exodus from the point of view of archaeology there are two important questions that archaeology might be expected to answer: the date of the oppression and the location of Mt Sinai. Unfortunately neither has yet been established beyond doubt, so here we shall attempt to examine the evidence and draw what deductions we can.

According to the Revised Chronology espoused by this website, Joseph entered Egypt during the reign of Sesostris I and was appointed to high office towards the end of Sesostris I's reign. We know that a certain Sobekhotep was treasurer in year 22, so the earliest that Joseph could have been appointed to that office was year 23. If we assume that Sobekhotep was displaced by Joseph, then the seven years of plenty came to an end in year 30 and there followed two years of famine before Jacob and his family arrived in Egypt. We will assume, therefore, that Jacob arrived in year 32, thirteen years before Sesostris I died.

The Bible indicates that there were 215 years from Jacob's entry into Egypt to the Exodus and the orange panel in table below shows how these years might be calculated. Note that the Exodus must have taken place 83 years after the end of the Twelfth Dynasty. By using different figures for the reign lengths, Dr Courville reaches the figure of 181 years to the end of the dynasty and a mere 34 years into the next dynasty.

| Twelfth Dynasty | Elapsed | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Amenemhet I | 29 | ||

| Sesostris I | 45 | 13 | |

| Amenemhet II | 10+ | 23 | |

| Sesostris II | 19 | 42 | |

| Sesostris III | 30+ | 72 | |

| Amenemhet III | 40+ | 112 | |

| (Unknown) | 8 | 120 | |

| Amenemhet IV | 9 | 129 | |

| Sobeknoferu | 3 | 132 | |

| Dynasty 13? | 83 | 215 |

Note that there is uncertainty about some of the reigns, so we may be a year or two out with Amenemhet II, Sesostris III and Amenemhet III and even more out if alternative figures are adopted for the lengths of reign. This just underscores the difficulty in reaching any firm conclusions about Egyptian history. It would hardly be worth mentioning this except that these figures will cause upset for those who would wish to have Sobeknoferu, the last ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty and the first known female ruler of Egypt as Moses' adopted mother.

It seems to me that Sobeknoferu is an irrelevance. The Bible does not claim that "Pharaoh's daughter" was anything other than a princess and although it might suit a certain dramatic scenario to consider otherwise, we have no grounds for such a supposition. It would appear likely that Moses' adopted mother, whoever she was, lived during the Thirteenth Dynasty (or, if the Thirteenth was contemporary with the Twelfth, during the Fourteenth). Egypt was still peaceful but its power was gradually waning as first the southern border was infiltrated by Nubians and then the Delta region split away from central control. It is even possible that the plagues inflicted on Egypt were the direct cause of the final collapse of the native Egyptian rulers, opening the way for the Hyksos to invade and establish the Fifteenth Dynasty.

This, however, provides an explanation as to why there is no mention of the Exodus in Egyptian records: there are virtually no records from these dynasties of any sort, so the absence of documents relating to the Exodus is not at all surprising.

During the Twelfth Dynasty there was a growing number of Semites in Egypt whose status is not entirely clear. By the Fourteenth Dynasty, which was confined to the Delta region, these Semites had become so influential that even some of the pharaohs had Semitic names, however during the Twelfth Dynasty it would appear that the majority of the Semites in Egypt were slaves. Because this was long before the Exodus by the conventional chronology, historians have never considered that these slaves might be the Israelites and are, therefore, puzzled as to how they came to be in Egypt. Immigration to escape wars or famine in Canaan have been suggested but it is not clear how voluntary immigrants come to be slaves. Captives taken in war is another suggestion, but there were very few invasions of Palestine during the Twelfth Dynasty and in any case, other wars in Palestine did not result in huge number of Semitic slaves!

By the Revised Chronology these Semitic slaves were the Children of Israel who had immigrated voluntarily into Egypt (as a result of famine in Palestine) and who were enslaved owing to fears that they might aid Egypt's enemies in time of war.

Exodus records that the enslaved Israelites built "treasure cities" called Pithom and Rameses, but Josephus adds that they were also made to work on irrigation schemes and on building pyramids. By conventional chronology this is impossible, because all the pyramids were finished long before 1445 BC - and in any case, the Israelites are famous for making bricks and the pyramids are made of stone!

The Pyramid Builders of Kahun

Interestingly there are two pyramids in the Faiyyum - at Hawwara and at il-Lahun - which are built of mud brick and the mud is mixed with chaff in order to bind it together. If Josephus is preserving a genuine folk memory, then it must be these Twelfh Dynasty pyramids which were built by the enslaved Israelites.

Dr Rosalie David of the Manchester Museum has written a comprehensive book about these Twelfth Dynasty pyramids, The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt, for they were excavated by Sir Flinders Petrie and many of the finds were given to the Manchester Museum. In particular, Petrie found and excavated the village, known as il-Lahun, in which the workmen had lived, where the house walls were preserved in some places up to eight feet high - and many of the doorways were spanned by the true arch, something that people thought was invented by the Romans!

Petrie observed that the workmen who built the pyramid were housed in a village that was surrounded by a strong, thick wall, but that an equally strong, thick wall divided the village into two parts: the larger part was on higher ground where it could catch any breeze and consisted of large, multi-roomed villas. The smaller part was made up of single-room dwellings packed into narrow streets, side-by-side and back-to-back. The village, he reported, reminded him of nothing so much as a Welsh mining village where the workmen lived in poor terraces on the valley bottom while the overseers and managers lived in large houses on the hill.

The fact that the village was surrounded by a strong wall is ambivalent: walls can serve to keep enemies out or to keep people in; the fact that two halves were divided by an equally strong wall pointed to the people in the poorer part being regarded with fear by those over them - in other words, they were not voluntary labourers working for pay but slaves.

Dr David mentions a grisly discovery made by Petrie:

Larger wooden boxes, probably used originally to store clothing and other possessions, were discovered underneath the floors of many houses at Kahun. They contained babies, sometimes buried two or three to a box, and aged only a few months at death.

Rosalie David, The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt, Plate 16

We know that Moses' mother kept her baby until he was a few months old and then, fearing lest his crying betray him and expose the whole family to pharaoh's wrath, she took him out and set him adrift on the river. At Lahun, where the slaves were shut in behind a strong wall, the desperate Israelite mothers did not have that option. Is it possible that some were forced to kill their own babies and hide the bodies beneath the floor? Certainly these tiny remains were not discarded carelessly, for with them were buried miniature grave goods to provide for their afterlife!

The greatest mystery about il-Lahun, however, is the fate of the workmen. Once again, this is how Dr David describes it:

It is apparent that the completion of the king's pyramid was not the reason why Kahun's inhabitants eventually deserted the town, abandoning their tools and other possessions in the shops and houses.

Rosalie David, The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt, p. 195There are different opinions of how this first period of occupation at Kahun drew to a close ... The quantity, range and type of articles of everyday use which were left behind in the houses may indeed suggest that the departure was sudden and unpremeditated.

Rosalie David, The Pyramid Builders of Ancient Egypt, p. 199

Dr David has no explanation for the sudden disappearance of the whole population of the village, but I have no doubt that they were Israelites who, in the exaltation of freedom, abandoned the tools with which they had been forced to work and took with them only what they could carry. One whole wall in the Petrie Museum of the University of London is devoted to the costume jewellery Petrie found in the village: some of the necklaces are pretty enough to be worn today - but why would the Israelite women take coloured stones, however pretty, when they could have gold?

The Lord said to Moses, "I will bring one more plague on Pharaoh and on Egypt. After that, he will let you go from here, and when he does, he will drive you out completely. Tell the people that men and women alike are to ask their neighbors for articles of silver and gold." The Lord made the Egyptians favorably disposed toward the people.

Exodus 11:1-3

The Midwife Shifrah

According to the Bible, the first step towards destroying the Israelites was when pharaoh ordered the Hebrew midwives to kill all male children.

| |

| This relief from Kom Ombo shows an Egyptian woman (or goddess) perched on a birthing stool. |

The term "delivery stool" was a puzzle to early Bible commentators, who were used to women giving birth in a reclining position. Egyptian reliefs, however, make it plain that women in Egypt gave birth seated on a special chair or "stool" which may have had a hole or cut-out in the seat through which the baby was delivered.The king of Egypt said to the Hebrew midwives, whose names were Shiphrah and Puah, "When you help the Hebrew women in childbirth and observe them on the delivery stool, if it is a boy, kill him; but if it is a girl, let her live." The midwives, however, feared God and did not do what the king of Egypt had told them to do; they let the boys live.

Exodus 1:15-17

There is a papyrus scroll in the Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn 35.1446) that gives a list of slaves, among whom is a certain "Shifrah". The name stands out because it is not an Egptian name. Unfortunately the scroll gives no further details about these slaves, so it is impossible to be sure whether the two references are to the same woman. The "Shifrah" of the scroll may be an entirely different person from the midwife of Exodus, but neither is it impossible that she was the woman who defied pharaoh's decree. Perhaps she was demoted from midwife to slave in consequence of her disobedience.

The interesting thing is that the scroll dates to the time of Pharaoh Sobekhotep III, a little-known ruler of the Thirteenth Dynasty. The Turin King-list gives him a mere four years of reign; on the other hand, he is known from a surprising number of inscribed objects and we even know the names of members of his family, among whom were a daughter called "Jewetibaw" who was allowed to write her name in a cartouche, a privilege usually reserved for the reigning pharaoh. She is only the second princess to receive this honour, which may imply unusual power. Perhaps she was Moses' adoptive mother?

Pithom and Rameses

The identification of the "treasure cities" has long been regarded as the crucial factor for dating the Exodus. Edouard Naville excavated Tel el-Maskhuta in the 1880s and found inscriptions giving the ancient name as "Pi-Tum". He also found storehouses which he attributed to the Israelites and statues of Rameses II, which accorded with the idea that the Exodus took place during the reign of Rameses. Subsequent excavations in the 1980s showed that the statues of Rameses had been brought from elsewhere long after that monarch's reign and that the site had been occupied by Asiatics in 1750-1625 BC (conventional chronology) and then abandoned until the time of Pharaoh Necho. The storehouses were from the Ptolemaic period!

Those who hold to an extreme view of Scripture must be puzzled to find patently false information mentioned in the Bible, albeit in passing and without any weight being attached to it. Clearly Paul was using the names as immediately recognisable shorthand for figures of rebellion against God and was not endorsing their historicity. |

Sir Allen Gardiner preferred Tel er-Rebata, but although other archaeologists such as Albright and Kitchen accepted his arguments, excavations failed to uncover any support for the identification.

Tel el-Maskhuta is attractive as the site of Pithom, but the Asiatics who inhabited it were from Middle Bronze II-III, which does not conform with either conventional chronology or the Revised Chronology.

Rameses is equally problematic. Modern thinking identifies it with Avaris, now known as Tel ed-Dab'a. Avaris also was excavated by Eduoard Naville in 1885 but the site wasn't regarded as particularly interesting until 1941 when Labib Habachi, an Egyptian archaeologist, suggested that it might be the long-lost Avaris. Excavations by the Austrians from 1966 onwards have confirmed this suggestion and made many interesting discoveries.

What is particularly interesting to us is that the site appears to have been founded in 1783 BC, which is the Thirteenth Dynasty and only 33 years before Pithom was founded. In view of the fact that pottery dating is, of necessity, an imprecise science, I wonder whether the two were not founded at approximately the same time.

A more serious problem is that the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, which includes the Twelfth and Thirteenth Dynasties, is placed in the Middle Bronze Age, whereas it is my contention that the Exodus occurred at the end of Early Bronze. The solution to the problem lies in the fact that although we speak grandly of "the Bronze Age", in fact there were different Bronze Ages as technology spread across the world. By conventional chronology, the Bronze Age began in Egypt around 3150 BC whereas it did not reach Mesopotamia until around 2900 BC. Thus Egypt might be well into the Middle Bronze while nearby Palestine was just starting that period.

The problem with the name "Rameses", which has led many historians to conclude that the Exodus must have happened during the reign of Rameses II, has been explained as dedicating the town to the god Ra long before there was a pharaoh of that name. A neater solution comes from Dr Donovan Courville who, in his tedious but masterly The Exodus Problem and its Ramifications, points out that every pharaoh had many names - most had five royal names or titles. After considerable research he discovered that the pharaohs of the Twelfth Dynasty had Rameses as one of their names. It follows, therefore, that if the name is important, then the pharaoh of the Exodus could have been one of these pharaohs or at least that the city was called after him. There is, however, the possibility that the city was actually called something else but had its name changed to "Rameses" and an editor inserted the "modern" name into the text in place of the original name. (Just as was done with with Hebron in Joshua 14:15.)

Another pointer to the Twelfth Dynasty instead of the Twentieth is the fact that Goshen appears to be in the Delta region (or possibly the Faiyyum!) and Moses returned to Goshen after his many encounters with pharaoh, while pharaoh sent messengers (or spies) into Goshen both to communicate with Moses and to see what was happening there. During the Twelfth Dynasty the capital of Egypt was near Cairo, so such journeys would be feasible. During the Eighteenth Dynasty - the time of the Exodus according to conventional chronology - the capital was at Luxor, 310 miles from Goshen as the bird flies and nearly 400 along the winding course of the Nile. Weeks would have elapsed between pharaoh deciding to summon Moses and Aaron and their appearance at the court, if they had had to travel 400 miles each way!

The Plagues and Ippuwer

Attempts have been made to link the Plagues of Egypt with the huge eruption of Santorini or Thera, but as more accurate dates have been obtained for that eruption it has drifted further and further from any possible date for the Exodus by conventional chronology and it is certainly not possible by the Revised Chronology.

A more interesting link with the Plagues comes from the Ippuwer Papyrus, which describes chaos in the land of Egypt and even mentions that "the river is turned to blood, no man can drink from it". The papyrus dates to the Nineteenth Dynasty but most scholars agree that it is a copy of an earlier papyrus and was probably first written some time between the Sixth Dynasty and the Second Intermediate Period (which followed the collapse of the Middle Kingdom). This is a very wide range indeed and allows it to be interpreted as referring to the First Intermediate Period or the Second Intermediate Period or various points in between.

Although it is impossible to prove anything, I believe that the Ippuwer Papyrus does indeed refer to the events following the Plagues and the author describes not just the Plagues but their aftermath as central authority collapsed and the Hyksos invaded.

Merneptah's Stele

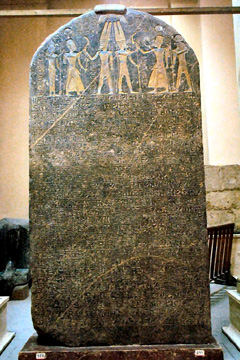

| |

| The Merneptah Stele in the Cairo Museum. |

The Stele of Merneptah was discovered in 1895 by Sir Flinders Petrie as he excavated the temple of Merneptah in Luxor. It is a long, bombastic text describing how the son of Rameses II repelled an invasion by the Libyans and generally terrorised the surrounding nations into accepting Egyptian sovereignity. Towards the end of the inscription is the only mention of Israel in the whole of ancient Egypt.

The princes are prostrate, saying: "Salaam!"

There is not one who holds up his head among the Nine Bows;

Since the Libyans are defeated, the land of the Hittites is in peace;

Canaan is purged from every evil;

Askalon is conquered; Gezer is held;

Yenoam is made as a thing not existing;

Israel is destroyed: it has no corn;

Khor is as a widow with regard to Egypt;

All lands are united in peace;

Every brigand is subdued.

The inscription has long been recognised as determining the latest possible date for the Exodus, for if Israel was already in existence in the time of Merneptah, then the Exodus cannot have occured during his reign nor in that of the eight Rameses who followed him. There is, however, another peculiarity about the inscription.

Egyptian hieroglyphs were a form of picture writing and every good scribe knew the correct symbols for "water" or "cow" or "house". However the pictures could also be used as letters of the alphabet to spell out foreign words such as the names of countries. In such cases the foreign word would be proceeded by a sign called a "determinative" which determined or showed the class of word that followed. For example, there were determinatives to indicate "woman", "god", "old man", "tree" or "grain". You can find some of these determinatives on the Omniglot website.

If I use the word halva it is possible that you will not have any idea what it means. It might be an exotic bird or flower or it might be the name of a pretty girl I met in Israel. If I were writing in hieroglyphs, however, I would put the determinative for "food" in front of halva and although you would still not know exactly what halva was, you would at least know that it was good to eat.

On the Merneptah Stele all the names like "Libya", "Hittite", "Gezer", "Canaan" and so on are proceeded by a flail, a stick with a bend at the top, which indicates that the words refer to foreign countries. In the case of Israel, however, the determinative is the second one on the Omniglot site - a seated man and woman, followed by another determinative of three vertical strokes, indicating "many" (the last determinative on the Omniglot site). In other words, "Israel" is the name of a numerous people, not the name of a country!

Experts in Egyptian say that this indicates that Israel is a not-yet-settled people and that therefore the reference in Merneptah's inscription shows that Israel was still wandering in the desert or in the early stages of the Conquest. Others suggest that the statement "it has no corn" refers to the fact that there was no food in the desert and that therefore Israel must be destroyed or nearly so. Still others analyse the inscription and point out that the places are listed from north to south and therefore conclude that Israel still must be south of Gezer, still wandering in the desert.

It is not for me to quarrel with these experts; I would point out, however, that all the other defeats and conquests mentioned are the result of Merneptah's prowess as a warrior - or claimed prowess - so the mere fact that Israel was wandering in the desert would hardly qualify them for mention, especially if they had so recently successfully escaped from Egypt's clutches! The use of "Israel" as a people could be in contrast to the northern and southern kingdoms after the days of Solomon or could refer to the fact that during the period of the judges there was no central authority that the Egyptians could recognise. In short, although the use of the determinative is interesting, one should not read too much into it.

reign of David Actually it is probably not the reign of David that is significant but the earlier time of the prophet Samuel. Such dates are always imprecise and it is more likely that Samuel undertook to compile the sacred books than that a warrior king, no matter how devout, should have done so. On the other hand, we have so little written material from before 1000 BC that it is possible that Classical Hebrew was, in fact, in use from the time of Moses onwards.

The earliest Hebrew writing yet discovered comes from Khirbet Qeiyafa above the Valley of Elah. The ostracon was excavated in July 2008 by the Israeli archaeologist Yossi Garfinkel and dates to around 1000 BC. The five lines of Hebrew appear to be in the Classical style and imply that the art of writing was well developed in Israel at the time. Returndifferent figures We have various sources for the kings of the Twelfth Dynasty (as for all the Egyptian dynasties) and they all give different reign lengths for the kings. Egyptologists prefer to accept figures based on archaeological finds - documents or monuments that mention the regnal year in which they were written or erected - but that is not always possible. For example, we have given the figure of 19 years for Sesostris II, but the latest regnal year attested by the monuments is year 8 and Egyptologists accept that that is clearly too short. Return

firm conclusions In this connection it is informative to read the article on Egyptian chronology on Wikipedia. My only complaint is that the article isn't radical enough! Another interesting site is run by Dr Peter James, author of the controversial Centuries of Darkness, which seeks to reduce the chronology of Egypt by 250 years. Again, I would wish to see a greater reduction, but his arguments have never been adequately answered and are still supported by Professor Lord Colin Renfrew. Return

first known female ruler Some have suggested that a Queen Nitocris may have ruled in the Sixth Dynasty and another five women have been proposed, all the way back to the First Dynasty, but Sobekneferu is the first woman known to have acted as pharaoh. Return

a certain dramatic scenario There is a popular theory that this princess was eager to adopt Moses because she had no natural child of her own (inbreeding in the royal line was to blame!) and her intention was that Moses should become the next pharaoh. However a distant male relative was waiting in the wings and eagerly took advantage of Moses' indiscretion in the matter of the native Egyptian overseer to stage what amounted to a coup de etat against Moses and, possibly, his adopted mother as well. Although it satisfies our love of the dramatic, I need hardly point out that there is not a hint of any such situation in the Biblical account. Return

"treasure cities" The Hebrew term misknah does not mean "treasure" but "storehouse" and certainly there were cities with large magazines, usually attached to the temples. However the Septuagint translates the expression as "fortified cities" and given the location of the two cities near the eastern border it may be that the fortifications were the most important aspect. No doubt Pharaoh regarded it as highly appropriate to employ the people he feared might join his enemies in constructing fortresses to keep those enemies out. Return

Twelfth Dynasty pyramids There are other pyramids belonging to the Twelfth Dynasty, but Kahun and Hawwara are the only ones in the Faiyum. Return